What if we found ourselves building something that nobody wanted? In that case what did it matter if we did it on time and on budget?

—Eric Ries

Epics

An Epic is a container for a significant Solution development initiative that captures the more substantial investments that occur within a portfolio. Due to their considerable scope and impact, epics require the definition of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and approval by Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) before implementation.Portfolio epics are typically cross-cutting, typically spanning multiple value streams and Program Increments (PIs). SAFe recommends applying the Lean Startup build-measure-learn cycle for epics to accelerate the learning and development process, and to reduce risk.

Details

This article primarily describes the definition, approval, and implementation of portfolio epics. Program and Large solution epics, which follow a similar pattern, are described briefly at the end of this article.

There are two types of epics, each of which may occur at different levels of the Framework. Business epics directly deliver business value, while enabler epics are used to advance the Architectural Runway to support upcoming business or technical needs.

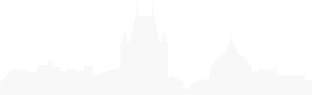

It’s important to note that epics are not merely a synonym for projects; they operate quite differently, as Figure 1 highlights. SAFe generally discourages using the project funding model (refer to the Lean Portfolio Management article). Instead, the funding to implement epics is allocated directly to the value streams within a portfolio. Moreover, Agile Release Trains (ARTs) develop and deliver epics following the Lean Startup cycle (Figure 6).

Defining Epics

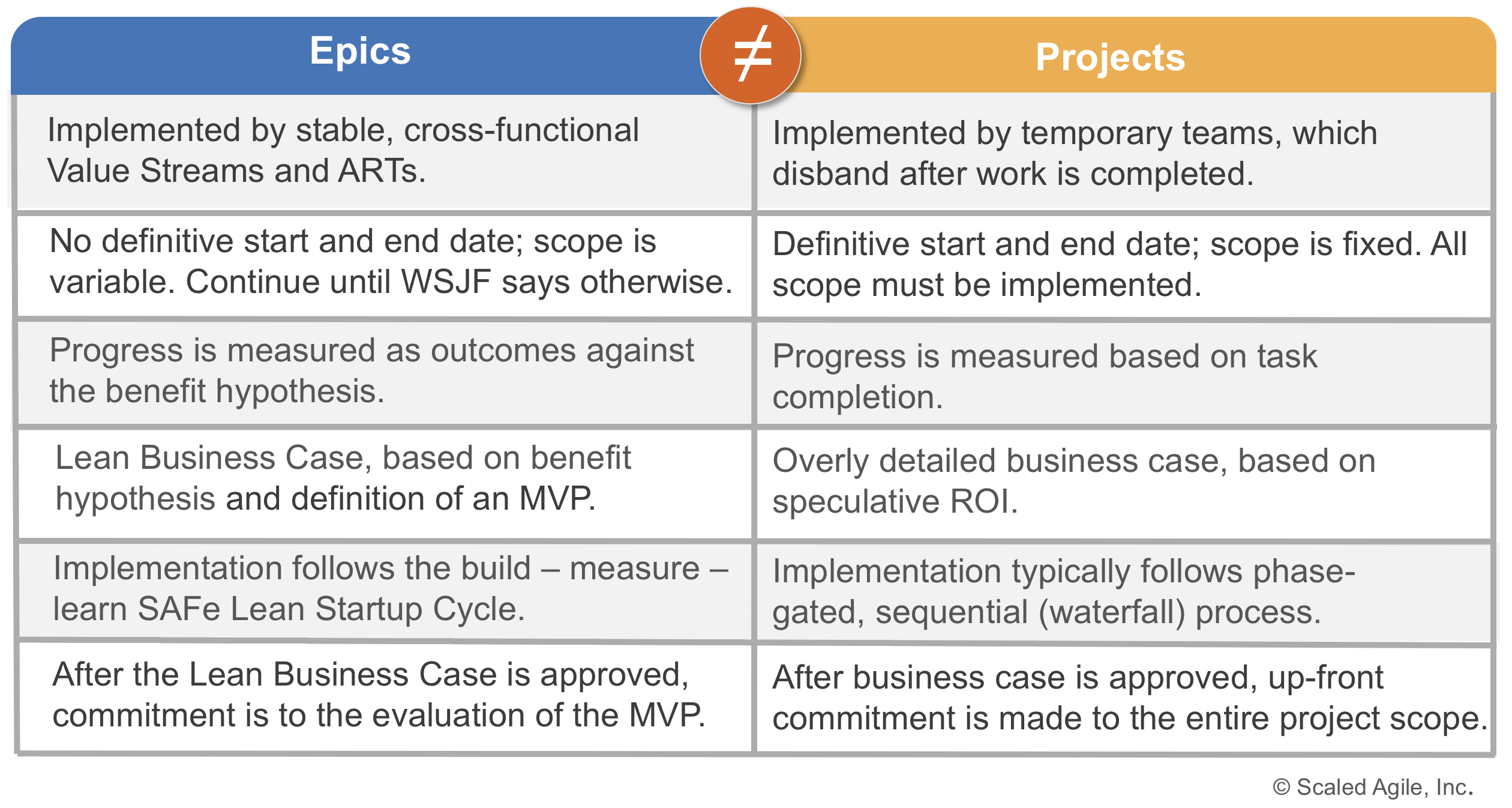

Since epics are some of the most significant enterprise investments, stakeholders need to agree on their intent and definition. Figure 2 provides an epic hypothesis statement template that can be used to capture, organize, and communicate critical information about an epic.

Download Epic Hypothesis Statement

Portfolio epics are made visible, developed, and managed through the Portfolio Kanban system where they proceed through various states of maturity until they’re approved or rejected. Before being committed to implementation, epics require analysis. Epic Owners take responsibility for the critical collaborations required for this task, while Enterprise Architects typically shepherd the enabler epics that support the technical considerations for business epics.

Defining the Epic MVP

Analysis of an epic includes the definition of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) for the epic. In the context of SAFe, an MVP is an early and minimal version of a new product or business Solution that is used to prove or disprove the epic hypothesis. As opposed to story boards, prototypes, mockups, wire frames and other exploratory techniques, the MVP is an actual product that can be used by real customers to generate validated learning.

Creating the Lean Business Case

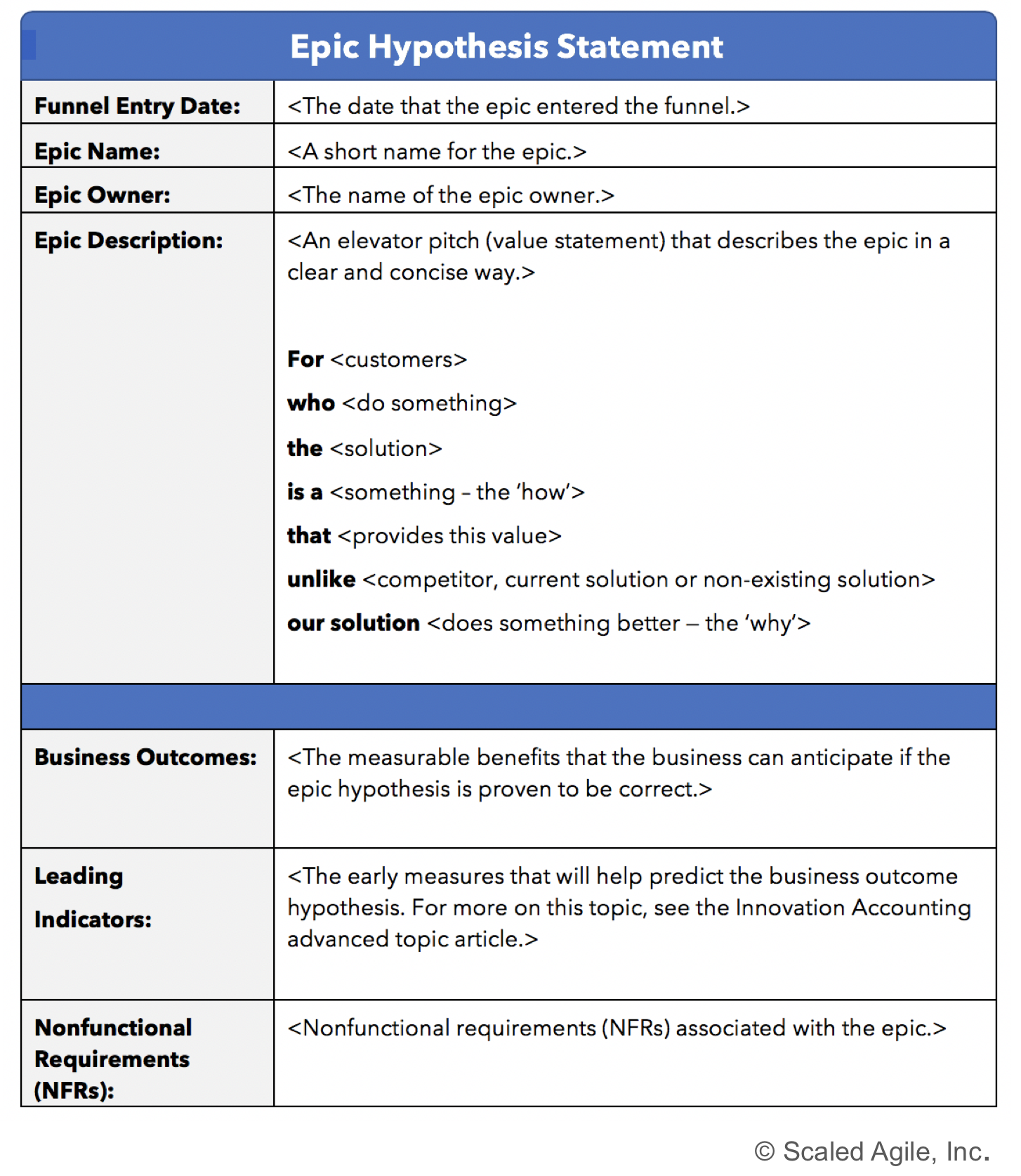

The result of the epic analysis is a Lean business case (Figure 3).

The LPM reviews the Lean business case to make a go/no-go decision for the epic. Once approved, portfolio epics stay in the portfolio backlog until implementation capacity and budget becomes available from one or more ARTs. The Epic Owner is responsible for working with Product and Solution Management and System Architect/Engineering to split the epic into Features or Capabilities during backlog refinement. Epic Owners help prioritize these items in their respective backlogs and have some ongoing responsibilities for stewardship and follow-up.

Estimating Epic Costs

As Epics progress through the Portfolio Kanban, the LPM team will eventually need to understand the potential investment required to realize the hypothesized value. This requires a meaningful estimate of the cost of the MVP and the forecasted cost of the full implementation should the epic hypothesis be proven true.

- The MVP cost ensures the portfolio is budgeting enough money to prove/disprove the Epic hypothesis and helps ensure that LPM is making investments in innovation in accordance with lean budget guardrails

- The forecasted implementation cost factors into ROI analysis, help determine if the business case is sound, and helps the LPM team prepare for potential adjustments to value stream budgets

MVP Cost

The MVP cost estimate is created by the epic owner in collaboration with other key stakeholders. It should include an amount sufficient to prove or disprove the MVP hypothesis. Once approved, the MVP cost is considered a hard limit, and the value stream will not spend more than this cost in building and evaluating the MVP. If the value stream has evidence that this cost will be exceeded during epic implementation, further work on the epic should be stopped.

Estimating Implementation Cost

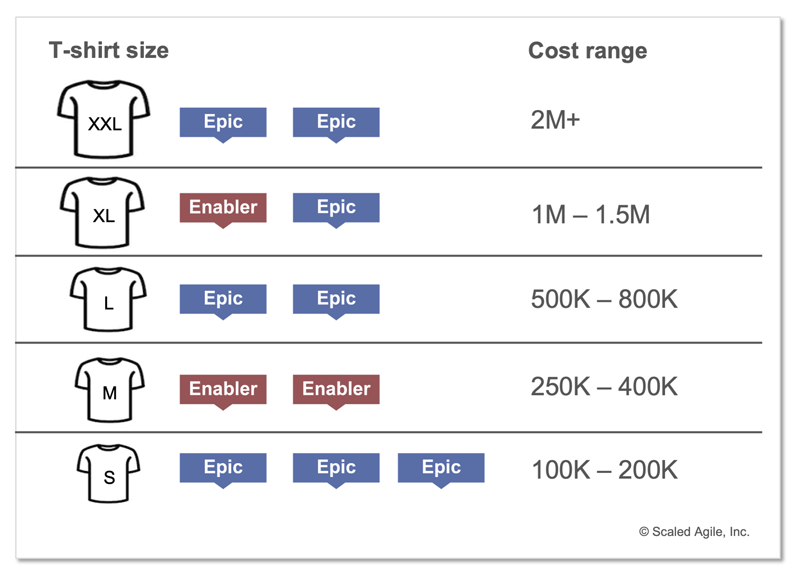

The MVP and/or the full implementation cost is further comprised of costs associated with the internal value streams plus any costs associated with external suppliers. It is initially estimated using t-shirt sizing (Figure 4) and refined over time as the MVP is implemented.

Estimating Epics in the early stages can be difficult since there is limited data and learning at this point. T-shirt sizing is a cost estimation technique which can be used by LPM, Epic Owners, architects and engineers, and other stakeholders to collaborate on the placement of epics into groups (or cost bands) of a similar size. A cost range is established for each T-shirt size using historical data. Each portfolio determines the relevant cost range for each T-shirt size. The gaps in the cost ranges reflect the uncertainty of estimates and avoid too much discussion around the edge cases. The full implementation cost can be refined over time as the MVP is built and learning occurs

Supplier Costs

An Epic investment often includes a contribution and cost from suppliers, whether internal or external. Ideally, enterprises engage external suppliers via Agile contracts which supports estimating the costs of a suppliers contribution to a specific epic. For more on this topic, see the Agile Contracts advanced topic article.

Forecasting an epic’s duration

While it can be challenging to forecast the duration of an epic implemented by a mix of internal ARTs and external suppliers, an understanding of the forecasted duration of the epic is critical to the proper functioning of the portfolio. Similar to the cost of an epic, the duration of the epic can be forecasted as an internal duration, the supplier duration, and the necessary collaborations and interactions between the internal team and the external team. Practically, unless the epic is completely outsourced, LPM can focus on forecasts of the internal ARTs affected by the epic, as internal ARTs are expected to coordinate work with external suppliers.

Forecasting an epic’s duration requires an understanding of three data points:

-

- An epic’s estimated size in story points for each affected ART, which can be estimated using the T-shirt estimation technique for costs by replacing the cost range with a range of points

- The historical velocity of the affected ARTs

- The percent (%) capacity allocation that can be dedicated to working on the epic as negotiated between Product and Solution Management, epic owners, and LPM

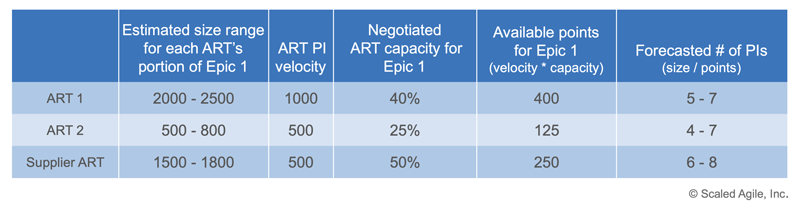

In the example shown in Figure 5, a portfolio has a substantial enabler epic that affects three ARTs and LPM seeks to gain an estimate of the forecasted number of PIs. ART 1 has estimated the epic’s size as 2,000 – 2,500 points. Product Management determines that ART 1 can allocate 40% of total capacity toward implementing its part of the epic. With a historical velocity of 1,000 story points per PI, ART 1 forecasts between five to seven PIs for the epic.

After repeating these calculations for each ART, the epic owner can see that while some ARTs will likely be ready to release on demand earlier than others, the forecasted duration to deliver the entire epic across all of the ARTs will likely be between six and eight PIs. If this forecast does not align with business requirements, further negotiations will ensue, such as adjusting capacity allocations or allocating more budget to work delivered by suppliers. Once the epic is initiated, the epic owner will continually update the forecasted completion.

Implementing Epics

The Lean Startup strategy recommends a highly iterative build-measure-learn cycle for product innovation and strategic investments. This strategy for implementing epics provides the economic and strategic advantages of a Lean startup by managing investment and risk incrementally while leveraging the flow and visibility benefits of SAFe (Figure 6).

Gathering the data necessary to prove or disprove the Epic Hypothesis is a highly iterative process that continues until a data-driven result is obtained or the team consumes the MVP budget. In general, the result of a proven hypothesis is an MVP suitable for continued investment by the value stream. Continued investment in an Epic that has a dis-proven hypothesis requires the creation of a new epic and approval from the LPM Function.

SAFe Lean Startup Cycle

After it’s approved for implementation, the Epic Owner works with the Agile Teams to begin the development activities needed to realize the epic’s business outcomes hypothesis:

-

-

- If the hypothesis is proven true, the epic enters the persevere state, which will drive more work by implementing additional features and capabilities. ARTs manage any further investment in the Epic via ongoing WSJF feature prioritization of the Program Backlog. Local features identified by the ART, and those from the epic, compete during routine WSJF reprioritization.

- However, if the hypothesis is proven false, Epic owners can decide to pivot by creating a new epic for LPM review or dropping the initiative altogether and switching to other work in the backlog.

-

After evaluating an epic’s hypothesis, it may or may not be considered to remain as a portfolio concern. However, the Epic Owner may have some ongoing responsibilities for stewardship and follow-up.

The empowerment and decentralized decision-making of Lean budgets depend on Guardrails for specific checks and balances. Value stream KPIs and other metrics also support guardrails to keep the LPM informed of the epic’s progress toward meeting its business outcomes hypothesis.

Program and Solution Epics

Epics may also originate from local ARTs or Solution Trains, often starting as initiatives that warrant LPM attention because of their significant business impact or initiatives that exceed the epic threshold. These epics warrant a Lean Business Case and review and approval through the Portfolio Kanban system. The Program and Solution Kanban article describes methods for managing the flow of these epics.

Learn More

[1] Ries, Eric. The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. Random House, Inc, 2011.Last update: 20 October 2022